What is a permanent closure?

A permanent closure is a fisheries management tool that establishes marine areas where fishing and harvesting of marine resources is permanently banned. It is sometimes also called a fish reserve, marine sanctuary, marine park, tabu area, no-take zone or no-take area.

What is the purpose of a permanent closure?

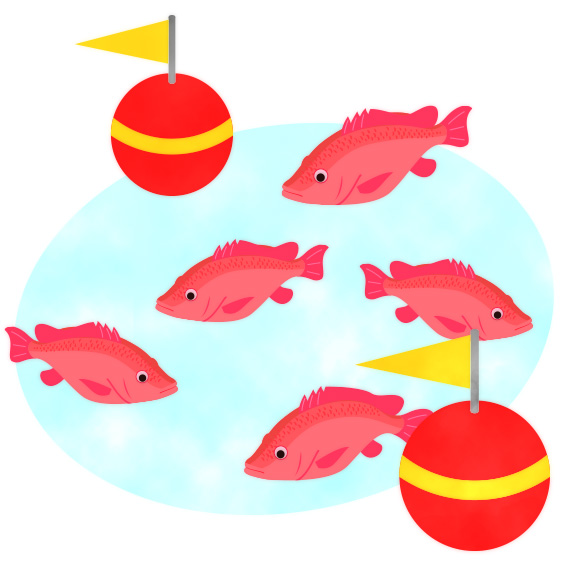

A permanent closure provides marine resources protection of their habitats, allowing them to reproduce. From the viewpoint of coastal and island communities, the aim of creating a permanent closure is to increase marine resource stocks, which will spill over into fished areas nearby, leading to increased catches. The movements of marine resources inside and outside an area closed to fishing and harvesting, is shown in the figure below. In this example, the adult fish in the no-take area produce young fish or larvae that drift through the water. Some larvae settle inside the no-take area, while others are carried away by the current and drift outside of it. Juvenile or adult fish may also move out of the closed area in response to increased crowding and competition.

When and where should permanent closures be used?

A permanent closure is a management tool to be considered when catches of specific marine resources have been decreasing. It is important to check whether the main species of concern are likely to benefit from a permanent closure (see species information sheets) or another management tool, such as a temporary closure. It is also important to consider how the marine resources are used by different individuals. It may be that one group, such as women fishers, will be more affected by a closure than other fishers and so their views and support should be sought.

Ideally, the closure should be positioned close to the community so that it can easily be monitored and protected from outsiders. In the figure below, a community has set up a closure in which fishing has been banned within its managed area. The no-take area should include a range of habitats such as coral reefs, seagrass and mangroves, which will benefit a variety of different species. In this example, the closed area is positioned so that the prevailing current flow is likely to distribute larvae and displaced fish into the fished area adjacent to the community.

How can we implement a permanent closure?

Permanent closures are preferably established and maintained by the communities themselves, as they have the most to gain. In some Pacific Island countries and territories, communities have control over the adjacent areas of coast and sea and can ensure that fishing bans in their closed areas are observed.

All members of the community must be involved in declaring a permanent closure to ensure awareness by all. The community bears the responsibility to mark the boundaries of the closed area with wooden stakes or buoys so that the area is clearly indicated. It also has the responsibility to enforce the permanent closure and penalise anyone breaking the community rules on fishing and harvesting.

Some countries and territories have open access fisheries in which there are no limits to where people can fish. In these cases, communities must be given the means to declare and maintain closed areas.

What are the benefits, problems and limitations of permanent closures?

Despite the positive effects of declaring permanent closures, some closed areas fail because they have not been established in suitable locations. Permanent closures positioned in areas of bare sand or coral rubble, for example, are unlikely to be successful as these are unsuitable habitats for most marine resources. Permanent closures are best declared in areas that include a variety of habitats and are sufficiently close to the community for their protection.

In a previously depleted area, it may take months, years or even decades for the numbers of marine resources to increase after the permanent closure has been declared. In this case, people in the community may tire of waiting for results and resent the imposition of the closed area.

> The increase in the numbers of marine resources is also not uniform across all species:

- Reef fish, such as parrotfish and snapper numbers may increase even in small, closed areas.

- Highly mobile fish, such as mullet and trevally, are less likely to increase.

- Among the invertebrates, faster growing species, such as trochus and small clams, appear to show greater recovery in closed areas than slower growing species, such as giant clams.

> Different fish species have varying ranges over which they move to feed; ideally the size of the closed area should be based on the local knowledge of the species.

Sometimes communities are tempted to open their permanent closure when they observe an increased number of marine resources for community celebrations; this defeats the original purpose of the permanent closure.

Although communities can often prevent their people from fishing in its declared permanent closure, it may be more difficult to prevent fishers from other communities from doing so. In this case, communities may need additional support from fisheries departments, agencies or the police for enforcement. In some cases, communities can use by-laws or community regulations which would allow offences to be punishable by law.

A community-owned and managed closed area requires resources, including labour and materials to mark area boundaries, and to enforce the fishing ban.

A permanent closure that is too large may deprive some people, particularly the elderly and women fishers, from catching their daily food. For this reason, it is necessary community members be involved in decisions in establishing the position and size of the closed area.

How do we know that a permanent closure is working?

The first obvious sign that a permanent closure is working may be by the simple observation of an increase of marine resource populations by community members, called perception-based monitoring.

There are more technical ways of determining increases in marine resources in a permanent closure. An underwater visual census (UVC) involves community members swimming in a straight line in several places across the permanent closure (wearing a mask and snorkel) and counting the number of marine resources of different species in a track of about five metres wide. The surveys can be kept simple by restricting observations to just five or six species. Surveys should be repeated at monthly intervals and the records of results kept and reported at community meetings.

UVC is especially appropriate if the community has external support to supply masks and snorkels and train young community volunteers to undertake these UVC transects across their permanent closure and then compare the results with those in unprotected areas.

What other management actions can complement a permanent closure?

Strong enforcement of bans on fishing and harvesting in the permanent closure area is necessary and particular community members are usually assigned to carry out this task. Protecting marine resources during their spawning season and enforcing size limits will also assist to increase the populations of these marine resources in other remaining areas of your fishing grounds. The fishing and harvesting of some marine resources are prohibited under national laws or regulations. These species require protection whether they are in a permanent closure or an unprotected area. Examples of these are humphead wrasse and bumphead parrotfish.

Communities may want to consider allowing fee-paying tourists to visit their well-preserved areas of corals and reef fish. While this generates income for the community, visitors should keep to marked tracks or snorkelling trails to avoid habitat damage.