Image: © Bradley Moore, SPC

To gain access to full information on reef sharks, download the information sheet produced by the LMMA Network and SPC.

Here are some priority actions the community can consider in addition to national regulations:

Fish smart rules

Fishing ban

Ban the local fishing of sharks for their fins. Insist that all sharks caught for food are bled and gutted and landed with their fins intact.

Tabu areas

Establish no-take areas for short periods where sharks are known to gather. These may include shallow-water nursery areas where young sharks are born – these areas are often known to local fishers.

Protecting marine ecosystems

Develop ecotourism based on ‘shark watching’. Tourists will pay to see non-aggressive sharks in their natural environment. A single caught shark may be worth a few dollars but the same shark left in the water may be worth many thousands of dollars if tourists pay to see it alive.

Gear restrictions

Regulate fishing gear. For example ban large-mesh gillnets used to catch sharks and ban the use of wire leaders to attach fish hooks to nylon fishing lines – sharks are able to bite through nylon and escape.

Good to know: sharks ensure a healthy reef

Because sharks produce only a small number of young, stocks can be easily overfished. Several species have been classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as threatened. Sharks are important in reef ecosystems as they remove weak and sick fish and thereby ensure that only the healthiest individuals are left to breed.

Fishing methods

In Pacific Island countries, sharks are caught using spears, baited hooks, gillnets and traps. Some traditional fishing methods have also been used, such as lassoing or noosing sharks in Tonga. Sharks are not eaten in some places, particularly in parts of Melanesia.

Although small reef sharks are not regarded as dangerous to humans they can be aggressive toward people spear-fishing or standing fishing in shallow water. Whitetip reef sharks, for example, are known to respond very rapidly to the sound of a speargun being fired.

Sharks retain urea (a nitrogen compound in the urine of many animals) in their blood and flesh and this gives a strong flavour to the meat. For this reason, the carcass of a freshly caught shark should be bled by removing the head and gills and thoroughly washing in seawater.

Sharks are fished in large numbers for their fins which are used in shark fin soup. Tens of millions of sharks are caught each year and in many cases their fins are removed and the rest discarded. This practice, called finning, results in a waste of fish flesh.

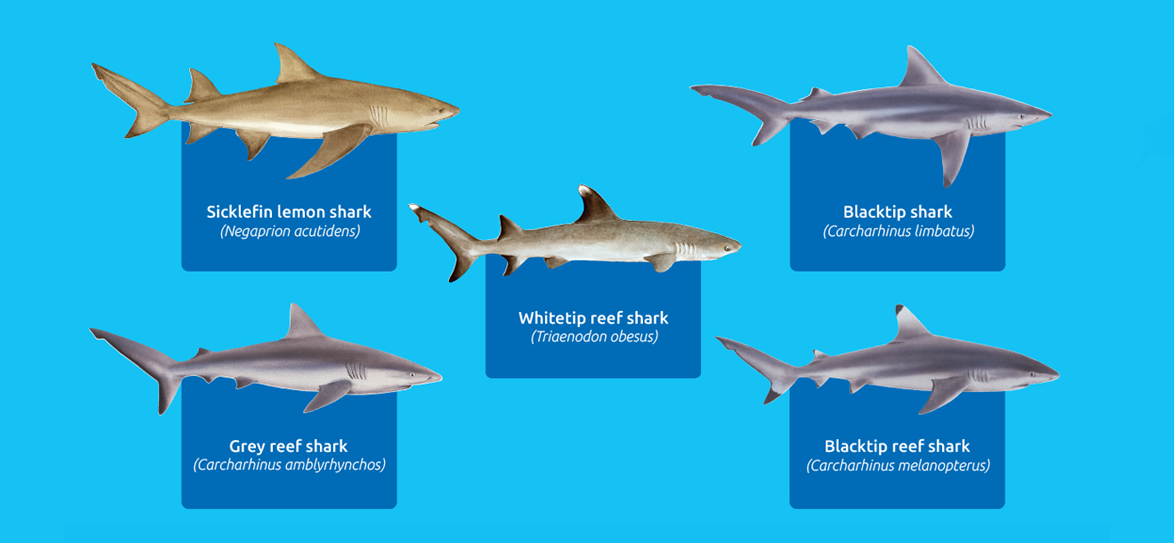

Some species

In the Pacific, inshore species caught by coastal communities for food include several species of small reef sharks (family Carcharhinidae). Common species include the blacktip reef shark, Carcharhinus melanopterus, the blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, the grey reef shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, the lemon shark, Negaprion acutidens, and the whitetip reef shark, Triaenodon obesus.

These smaller species have a wide distribution in the IndoPacific and, other than the lemon shark that grows to three metres, most reach a size of about two metres. Several other larger and more dangerous species, including tiger sharks and bull sharks, are caught, mainly by commercial fishers.

Most of these sharks swim continually to obtain oxygen from water flowing over their gills; the whitetip shark, however, can pump water over its gills and lie motionless on the sea floor.

Generally, small reef sharks prefer shallow, inshore areas including reef flats and coral reefs. Young sharks may live in inshore areas that offer plentiful food. Most species remain one particular area though blacktip sharks move over considerable distances.

Most reef sharks hunt alone but can form feeding frenzies when people spear or gut fish in the water. Reef sharks eat fish such as sardines, mullets, mackerels, trevallies and emperors as well as octopuses and shrimps. Whitetip reef sharks often rest under coral during the day and hunt at night.

Small reef sharks are eaten by larger fish including sharks and groupers.

Sharks have separate sexes and males have two external sex organs called claspers located beneath the body just in front of the tail. During mating, a male inserts one of his claspers into the opening (cloaca) of the female to transfer sperm packets (spermatophores).

The female carries the young developing sharks within her body and gives birth to up to ten live young sharks, about 65 cm long, a year or so later. About nine out of every ten young sharks die before moving out of shallow inshore areas.

Sharks reach maturity after eight years and at a length of about one metre. Most species reach a maximum size of about two metres in approximately 12 years. After mating, females may return to the shallow water areas where they were born to give birth themselves.

Related resources

To gain access to full information on reef sharks, download the information sheet.