Image: © Pauline Bosserelle, SPC

To gain access to full information on spiny lobsters, download the information sheet produced by the LMMA Network and SPC.

If you have noticed a decline in your catches or are concerned about spiny lobster populations, here are some priority actions the community can consider in addition to national regulations:

Fish smart rules

Quotas

Restrict the total community catch of lobsters to a sustainable level. A sustainable catch may be as low as 20 kg of lobster per km of reef-face per year;

Tabu areas

Rotate the catching of lobsters on different areas of reef. Each area could be fished for 1 year and then left unfished for a number of years;

Size limits

Ban the taking of small lobster (enforce national minimum size limits);

Gear restrictions

Ban the use of underwater breathing apparatus;

Ban the use of spears. Collecting lobsters by hand allows fishermen to avoid small lobsters and live lobsters are more marketable than dead ones;

Fishing bans

Ban the taking of female lobsters carrying eggs

Good to know: neighbouring communities should enforce the same management measures for spiny lobsters

Management of lobsters by individual communities is often difficult because the small drifting (larval) stages float in the sea for a very long time (often, over a year) before settling on reefs as juveniles. Therefore, the young produced by adult lobsters in a community’s fishing area may settle on reefs some distance away.

If an atoll or a small island community takes actions to manage its lobster fishery, these are likely to benefit local fishers. If only one of many communities on a long coastline takes management actions, lobster numbers may still decrease if other, nearby communities have depleted their own lobster numbers. In this case, the best solution is for many neighbouring communities to work together and agree to the same management measures.

Fishing methods

In most Pacific Islands, the main fishing method used is the collection of lobsters by hand or by free diving at night with underwater lights. Some lobsters are taken by the use of spears and, unfortunately, underwater breathing apparatus is sometimes used.

Many large-scale operations to catch lobsters in Pacific Islands have failed because the main species are generally present in low abundance and, except for the Hawaiian spiny lobster, do not enter traps or pots readily. It is important that fishery authorities reserve lobster fishing for local people selling to local markets.

Management measures in the region

Fishery authorities have applied minimum size limits on various species and these are available here, by selecting size limits in ‘select regulations’ and filtering by species. National size limits are particularly useful if lobster catches can be checked at relatively few market places.

Some authorities have banned the taking of egg-bearing females and soft-shelled lobsters. Some have applied catch or bag limits (for example, 10 lobsters per person per day), banned the use of underwater breathing apparatus, and banned the export of lobsters.

Some species

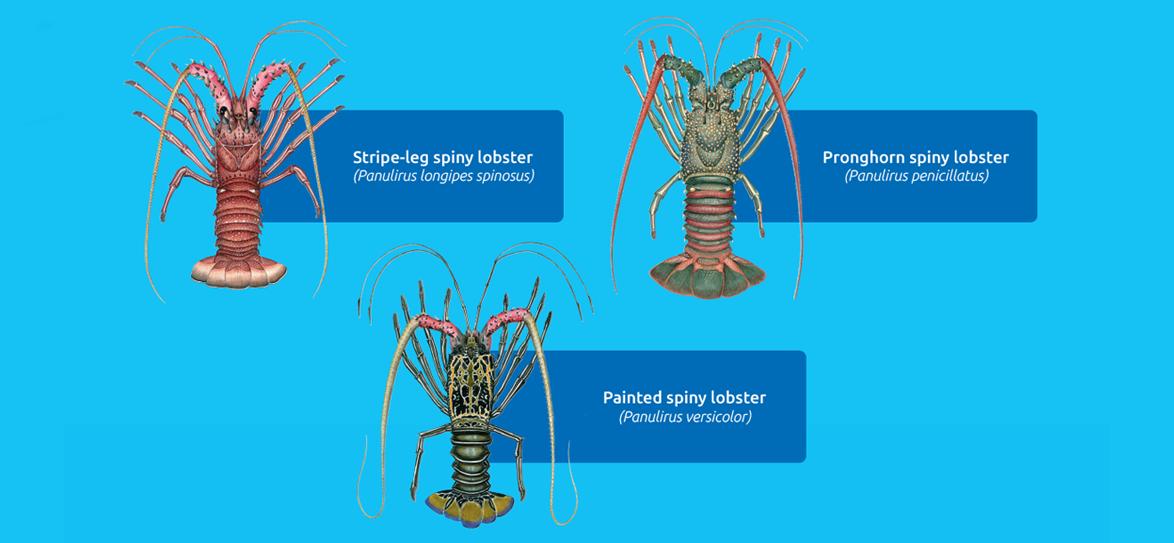

Unlike true lobsters, spiny lobsters do not have large claws and are found in almost all warm seas. Those of interest in Pacific Islands belong to the genus Panulirus.

There are six species in the Solomon Islands, but only one, the pronghorn spiny lobster, Panulirus penicillatus, ranges out to eastern Polynesia. Except in Papua New Guinea, where the ornate lobster, Panulirus ornatus is caught, the main species caught are the pronghorn spiny lobster mixed with smaller quantities of the stripe-leg spiny lobster, Panulirus longipes spinosus. The painted spiny lobster, Panulirus versicolor is of minor importance.

Spiny lobsters live in crevices on reefs and move out at night to feed.

The pronghorn spiny lobster lives in the outer surf zone and moves onto the reef flats to find food. The stripe-leg spiny lobster lives in deeper water. The painted spiny lobster lives among the corals as well as in deeper water on outer reef slopes. The ornate lobster is found from shallow lagoons to continental shelves.

Spiny lobsters feed on sea snails, clams, crabs, sea urchins, plants (coralline algae) and dead animals. They are eaten by large fish, sharks and octopuses.

The different species of Pacific Island lobsters have similar life cycles. They have separate sexes and, depending on species and location, reach reproductive maturity at around 80 mm carapace length. They become mature adults within 3 to 5 years and live for about 10 years.

Many species appear to breed throughout the year, sometimes with a peak in the warmer months of the year. A male deposits a sperm packet (spermatophore) on the underside of a female. The female releases many thousands of eggs which are fertilised as they pass over the sperm packet. The fertilised eggs are carried for about a month before they hatch into very small floating forms (the larval stages). These drift in the sea for a year or more, and less than one in every thousand survives to settle on the sea floor as a young lobster (juvenile). And less than one in every hundred juveniles survives to become a mature adult.

Related resources

To gain access to full information on spiny lobsters , download the information sheet.